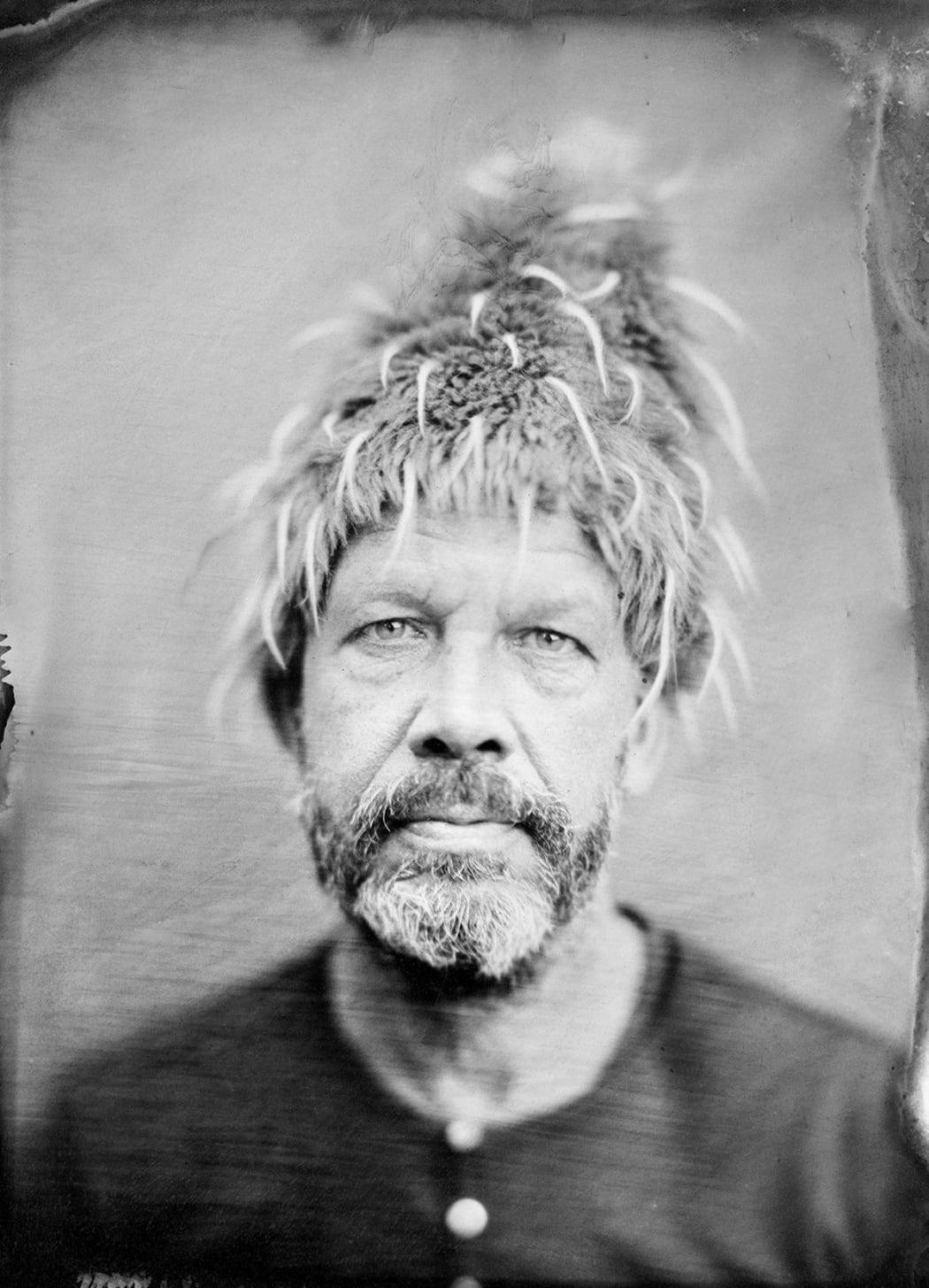

We asked Allan Barnes, a San Jose-based photographer and educator, a few questions about his decades-long career exploring historic 19th century photography processes and image making. Allan's solo show, Meditations, will be on view from January 10th through February 23rd, 2025. The opening reception will be held on Saturday, January 11th from 4-6pm.

What got you interested in wet-plate collodion?

Great question! I started my life as a photographer documenting the city I grew up in, which was gradually disappearing. Detroit was the Silicon Valley of a century ago, a place of innovation, where all of my grandparents moved to start their adult lives. By the time I arrived, in the early 1960s, the auto industry lacked any new ideas or innovation and was dramatically withering. The flight of the middle class meant that the city that I grew up in lost half of its population. I started using a large format camera to document the landscape and architecture of my hometown before it vanished.

Then I became a photojournalist. Late in my photojournalism career a mentor who gave me my last magazine staff job challenged me - Why do you shoot everything in 35mm? Why don't you try using medium format and Polaroid? I followed his advice and started using lots of Polaroid Landfilm (older Polaroid peel-apart film). I used Polaroid Type 55, a 4x5 inch film along with medium format Polaroid Type 665 and Polaroid 669 film. I was doing something called 'Polaroid Transfers' a lot. I even enjoyed a couple of years being a Polaroid Creative Uses Consultant but then Polaroid went bankrupt and their best instant film types went extinct. I went through a "Damn, what am I going to do now," period then saw a micro-trend around 2004 - a little spike in artists using older photographic technologies such as wet-plate collodion and even Daguerreotypes.

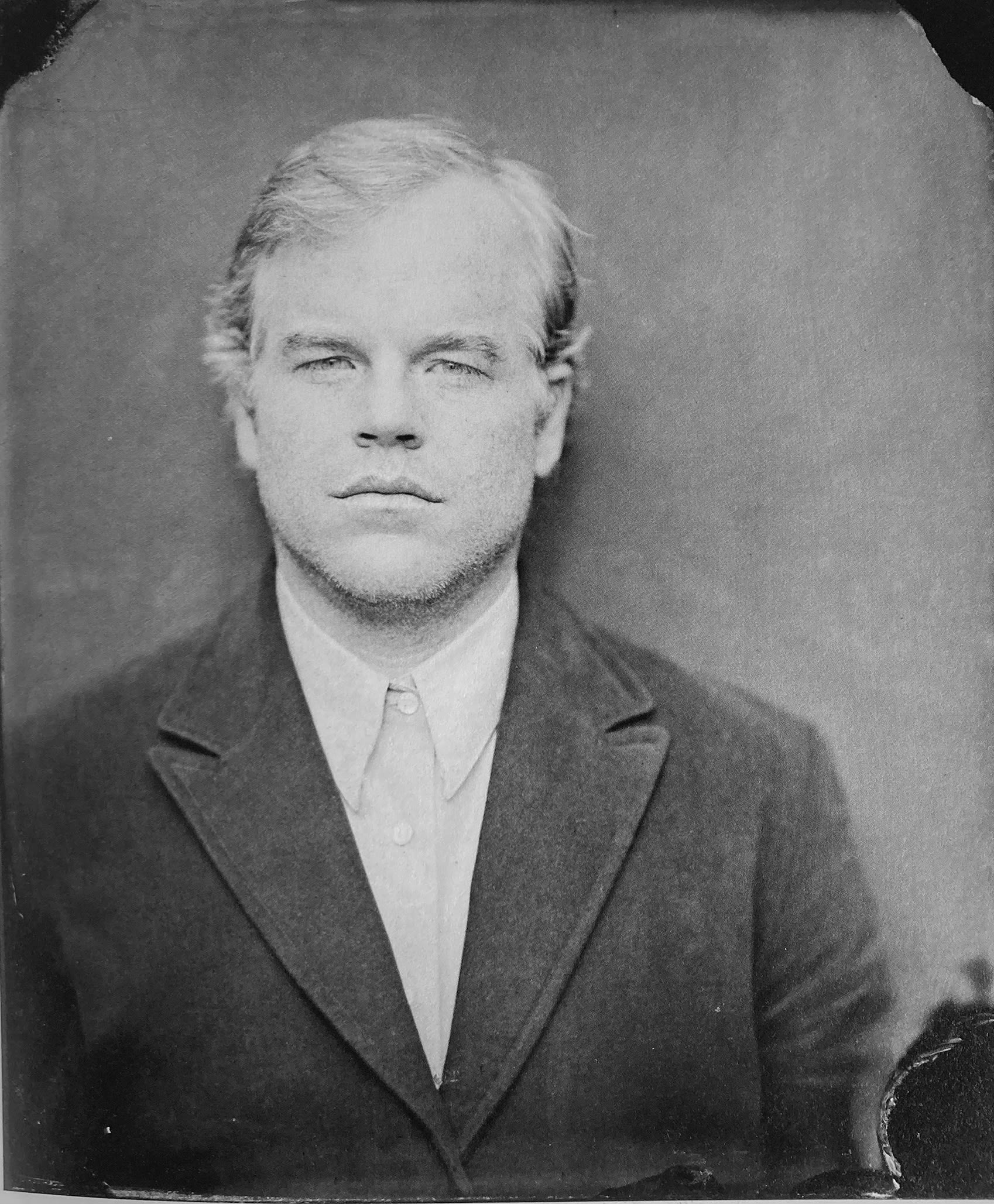

When I first thought about making Daguerreotypes, I balked when I learned how incredibly labor-intensive it was, plus the fact that you had to heat up Mercury, which is kind of the poster child for toxic metals! Then I saw an Ambrotype of the actor Philip Seymour Hoffman by photographer Robert Maxwell… It was a light bulb moment. After taking a couple of workshops, the first with Joni Sternbach, and the second with John Coffer (both prominent, long-established wet-platers) I decided to plunge into it. The physicality of the process reminds me that I did not become a photographer to sit still.

What are the physical challenges of using this medium and how do you plan for the unpredictability of the process?

The process of wet-plate collodion is from before the era of mass production in the United States. When this process was invented, the fastest rate of speed that most ordinary humans could travel was at the speed of a horse… or perhaps a train. Wet-plate collodion is easy to do badly and challenging to do well. You are manufacturing your own chemicals and media on the spot… The ISO is less than one, and the process only likes the middle of the light spectrum. It's 'orthochromatic' much like early silent films, with a reduced scale of greys, so that in silent films the actors would have black lipstick and dark makeup to add contrast, and I often have my subjects use dark makeup to compensate for the reduced tonality.

How did you shift from photojournalism to making photos from an artistic perspective?

It was easy: the amount of paid assignments available for photojournalists has been decreasing for decades now, print media is a dinosaur, and now we have an incoming administration that regularly incites its fans to attack journalists. My identity as a photographer used to be confirmed by publications calling me and giving me photo assignments. I grew to hate winters in Detroit and decided to move to California, so I had to reinvent myself - that's what you do when you move to Los Angeles as a middle-aged person!

I moved into a huge shared loft just outside of downtown LA in 2008, and having just learned the process, I had an enclosed garden for a studio, a bedroom that was also my darkroom, and neighbors in the building who were working artists and would gently poke you if you were just sitting in the garden with comments like "Good morning! Working on anything interesting today?" I had always done "artistic work" on the side, but it became my primary genre of photography.

You've mentioned collaborating with artists, designers, and models to create your figurative work. Can you talk about the collaborative process that goes into creating your portraits?

Well, I previously mentioned moving into a space near downtown LA where six of us shared a huge loft - it was 2009, there was a recession, and working alongside such a great community of creative people who used both personal connections and social media to connect with like-minded people resulted in some amazing collaborations with clothing designers, body painters, set designers, etc… we had some amazing team projects. That was very refreshing!

What drew you to start photographing landscapes? How do you choose which locations to shoot?

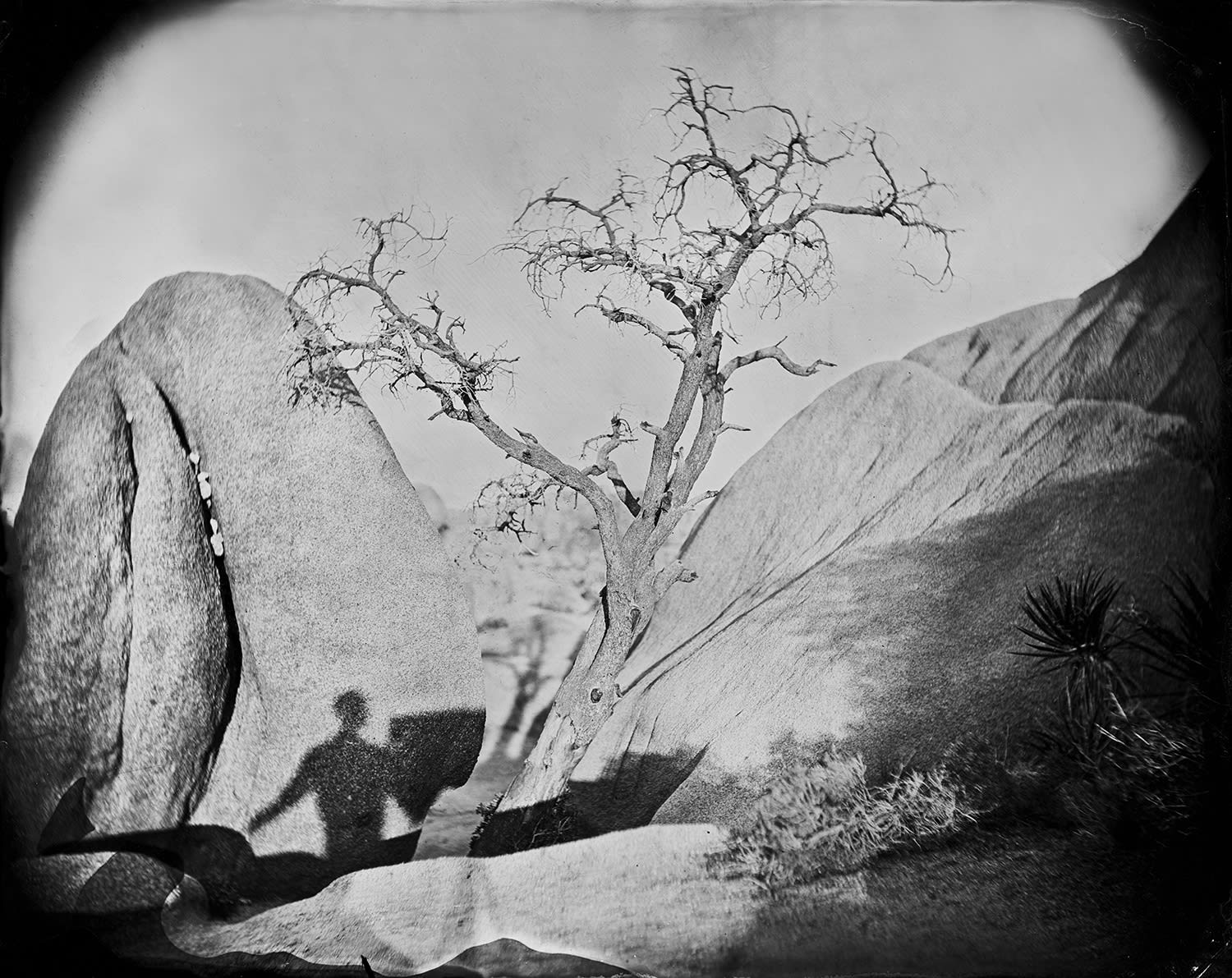

Ha! Another Detroit story. In 2009, a friend named Sherry Hendrick (who had a gallery in a rebuilt multiple-car garage in Detroit) asked me to be in a landscape art show. My reaction was, "Oh thanks, I really don't do landscapes." Sherry's reaction was, "Well, go do some, you live next to the LA River, go take some pictures of it!" It was a great challenge. I coated and developed the plates in the shell of my old beater Ford Ranger pickup - the most uncomfortable darkroom ever. I had some cool work for that show. So next I got an ice fishing tent and did some work at Joshua Tree National Park, Pescadero, and Yosemite. The tent darkroom would sometimes get pummeled by wind, or I would set it up in a shady place only to have the sun hit it a few hours later, but it was still worth all the trouble.

I set my sights on having an old Toyota Camper for a mobile darkroom and bought one in 2018. My favorite place to prowl is the Pacific Coast Highway. I feel like there are parallels in beauty between Detroit and California, but the beauty of California is natural. Having the good fortune to live so close to so many of these places is humbling.

If you could photograph any location in the world where would you go?

I think that you have to divide that into two questions - 'If you could return to anywhere that you visited in the world would you return to as a photographer?' and 'What place that you have never been to would you like to go to as a photographer?' - and that would be Bolivia and Peru, respectively.

As a high school digital media teacher, how does teaching inform your artistic practice?

My students are a joy to be with and my classes are modeled a bit after my life as a creative professional. It is great to be part of an educational community, and I work at Sobrato every day with a great community of educators and staff. The secret of teaching is that you are getting paid to learn. I am of course a little behind on some of the new tools in Adobe Photoshop, and I wouldn't care about it so much, but I also have to keep up with the new stuff - it's good to stay on your feet and move quickly through the line at the banquet of technology.

What are your thoughts on 'tech fatigue' and the widespread turn to film photography in the past few years? Do you think there's an inevitable future where the medium of photography will overwhelmingly return to analog processes?

No, of course not! The formula of easier-faster-cheaper replaces harder-slower-more expensive is well established and practical. There are people who get angry at changes in technology, I try not to be one of them.

It's funny, but I don't miss film that much, and I am thinking about the time that I spent developing rolls of film and asking, "Why would I do that again?" Yet here I am using a technology that's 50 years older than film and many times more time-consuming. I think that it's the draw of the physical. My first love before photography was woodworking, I grew up watching my grandfather and his brothers building and creating with wood.

Anybody can carry a camera in their pocket to take photographs of the amazing California landscape, but when you are making multiple trips to carry your tripod and camera down a steep bluff, then running back and forth to the darkroom RV to develop your plates and prepare new ones, and you do this fifteen or twenty times in a day.

I compare the addictive nature of this to the addictive nature of gambling. Gamblers get addicted by 'random reinforcement'. It is one of the most powerful reinforcements because of how infrequently the actual reinforcement occurs. When it does occur, all you can think of is how quickly you can get another. Wet-plate collodion gives you an addiction that also increases your rate of physical exercise. This is a perfect excuse in case anybody brings up your addiction in casual conversation.